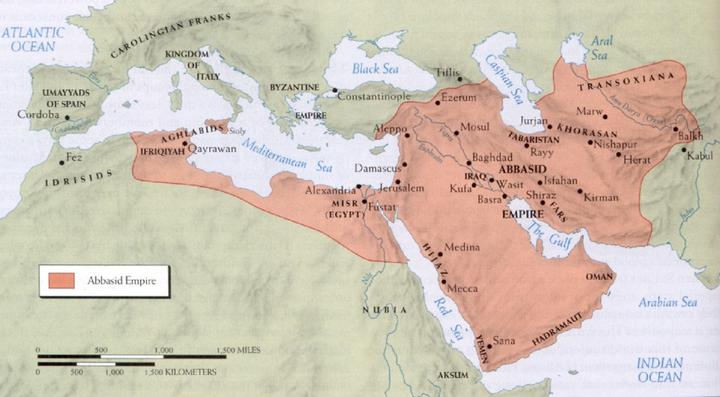

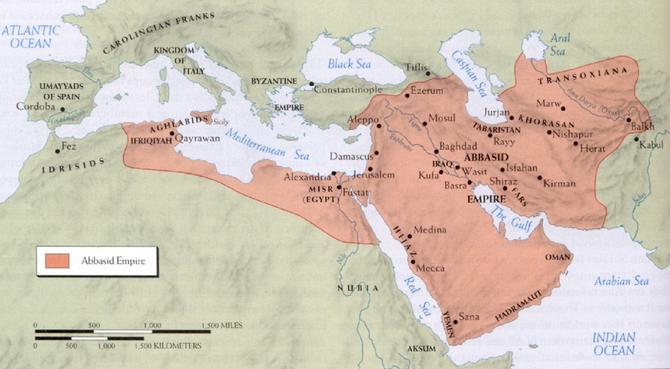

The Abbasid caliphate (or the Bagdad caliphate) is a feudalistic theocratic state which existed from 750 to 1258 with the ruling dynasty of Abbasids. The state included the territory of modern Arabic countries in Asia, part of Central Asia, Egypt, Iran, and North Africa. This dynasty edged out the Umayyads; they claimed for the supreme power reasoning it with the fact that the Umayyads – though the descendants of the Quraysh tribe – did not belong to the kin of the Prophet Muhammad. At the same time, the Abbasid traced their origins to the uncle of the Prophet Al-‘Abbas ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib from the kin of Hashim.

Originally the Abbasids did not play any significant part in state affairs. But as the caliphate grew more and more disaffected with the ruling dynasty of the Umayyads, the significance of this kin increased. Owing to their close relationship to Alids, the Abbasids could count on the support in the side of the Shiites. At the beginning of the 13th century the great-grandson of Abbas, Muhammad ibn Ali ibn Abdullah succeeded in earning support from several Shiite clans which recognized him as the Imam.

When the Abbasid dynasty replaced the Umayyads, a considerable amount of changes were made in administrative, military, political and scientific spheres. The year 750 when the Abbasids swept to power became one of the major turning points in Islamic history. The Abbasids’ accession to power was only possible as a result of actions of big well-organized groups and coordinated propaganda on the side of their leaders. The propaganda was made among those social groups that were discontented with the reign of the Umayyads. Political commitments and laws that were kept by the Umayyads throughout a hundred years gave rise to numerous disaffected masses in the overgrown Islamic society. These disaffected social groups eventually contributed to declining of the Umayyads.

An Islamic state founded by the Prophet Muhammad consisted mainly of Arabs; the number of “non-muslims” living on that territory was rather small. As a result of conquests made in the days of pious caliphs, the Islamic territory expanded to Egypt, Syria, Iraq, and Iran. Crusades of conquest continued during the reign of the Umayyads, too, and the territory of the caliphate reached Andalusia and inner parts of Central Asia. Arabic conquerors admitted the right of the locals to profess their religions, but in this case, local residents had to pay a special tax for “non-muslims”, and those locals who accepted Islam were entitled to enjoy the same privileges as Arabs.

Islam implied the supremacy of the state, but the Umayyads introduced another model of ruling based on the certain cohort of ethnic Arabs. Thus, having spread far out of its borders, the caliphate gradually turned into a state guided by an ethnic group. During the rule of the Umayyads Arabs became a separate social class released from debts. The majority of military leaders were Arabs, and they were the only ones to obtain monetary allowances, monthly and annual payments and shares of war trophies.

Non-Arabic residents of conquered territories who had adopted Islam were considered to be “lesser human beings” in respect to social, economic and career facilities. In theory, these people had the same rights as Arabs did, but in fact, it was not so. In fact, they suffered various types of derogation including lower payments for crusades and extra taxes. Such practice triggered the formation of strong opposition for the current government.

The Abbasids secretly prepared for dethroning the Umayyads sending their agents all over the empire. The real center of the anti-Umayyad movement was in Kufa; except that, the Abbasids found fertile ground for their propaganda in Khorasan and Mawarannahr among the Shiites. As a result, the Abbasids took advantage of the anti-Umayyad Shiite uprising and dethroned the dynasty. Ira Lapidus, the historian, wrote that the Abbasid found great support among Arabs, chiefly the dissatisfied Marw settlers, a group of the Yemeni and their non-Arab Muslims” (Lapidus). The Umayyad intestine strife that flared up after the caliph Hisham’s death in 743 was fuel for the Abbasids’ victory. The last Umayyad caliph reigned the western part of the caliphate till he was killed in 750.

The Abbasids’ reign can be divided into four periods: the period of prosperity (750-861), the period of decline (861-946), being under the sway of Buyid dynasty (946-1075) and being under the sway of Seljuq dynasty (1075-1194). Abbasid dynasty reached its Golden Age during the reign of such caliphs as Al-Mansur, Al-Mahdi, Harun Al-Rashid, and Al-Ma’mun. With the Abbasids in power, the nature of the supreme power underwent certain changes: caliph turned from the leader of the Muslim army to the head of the whole Muslim community where denomination weighed more than ethnicity. In this period many non-Arabic people got high positions in the state; it brought revival and prosperity to national cultures. The increase of feudalistic oppression triggered popular uprisings led by Babak, Al-Muqanna, and others.

The capital of the empire was moved from Damascus (Syria) to Baghdad (Iraq) which was founded in 762 on the river Tigris; during the period from 836 to 892 the capital was located in Samarra. In general, this dynasty made an effort to revive the Persian administrative system; in particular, they revived the position of vizier. A new position of the vizier was also established to represent central authority and was local emirs were entrusted with even greater powers. In the long run, many Abbasid caliphs were now granted a more nominal role than during the reign of the Umayyads, as the viziers exercised stronger influence, and the old Arab aristocracy ceded its influence to Persian bureaucracy (University of Calgary, 2008). However, such spheres as education and courts were entirely outside the vizier’s competence, they were run by clergymen and qadis (judges). The peculiar feature of the Abbasids’ religion politics was the tendency to preserve the balance between various Islamic movements and non-Arabic cultural traditions.

Army took a special place in the caliphate and also it changed considerably. Arabic soldiers of Bedouins were replaced with a better organized mercenary army that included professional warriors of Berbers, Turkic and Khorasan people. Arabic military forces played a minor role. The main place of military hierarchy was now occupied by the caliph’s guards consisting of Gilman: they were slave-soldiers brought to the empire from far away, bought or acquired as trophies from conquered peoples; Turkic, Caucasian and Slavic youngsters who were brought up and taught to be perfectly loyal to the caliph. Deeply devoted to the caliph in the beginning, the guards later felt their power and began to dictate their will to him and even to chair their own leaders.

However, the epoch of the Abbasids is considered to be the Islamic Golden Age. In virtually every field of endeavor —in astronomy, alchemy, mathematics, medicine, optics and so forth — Arab scientists were at the forefront of scientific advance (Huff, 2003). As the Abbasids ascended to the throne and transferred Baghdad to the capital the caliphate stepped into the period of flourishing. The dynasty was strongly inspired by the injunctions stated in the Qur’an and Hadith that emphasized importance and value of knowledge, for example, the one stating that the ink of a scientist is more valuable than a martyr’s blood, that is, the stressing the value of knowledge (Gregorian, 2003). This period is also referred to as the Renaissance of Islam (Kraemer, 1992).

During the Golden Age Muslim scholars, artists, engineers, poets, philosophers, and merchants contributed to science, economics, literature, philosophy, agriculture etc. either preserving traditions of the past or using their own inventions. Both during the reign of the Umayyads and the Abbasids governors lent substantial support to scholars. The practical importance of medicine, military hardware, mathematics stimulated the development of the Abbasid caliphate. Arabic language with its specific precision became a universal language of science because it was perfect for scientific and technical terminology. The scholars from different countries – from Cordova to Baghdad had an opportunity to communicate in one language. In the 9th century, numerous meetings were held by the governors of Baghdad where theologians, philosophers, and astronomers regardless of religious affiliation gathered in order to discuss their ideas. During this period of time Muslim civilization was a cauldron where the knowledge from Rome, India, China, Egypt, Greece, Persia, and Byzantium was collected, mixed and advanced.

The reigns of Harum Al-Rashid and his successors – in particular, his sons Al-Mamum and Muhammad Al-Mutasim – are thought to be the period of significant intellectual and scientific achievements. A certain number of medieval Islamic scholars played an important role in sharing acquired knowledge with the Christian West. In their turn, European colleagues contributed to the Arabic civilization by translating works of Greek thinkers from Greek to Syriac and later – to Arabic language (Hill, 1993).

Although Muslim scientists made a significant contribution to geography, mathematics, biology, and astronomy, they were especially successful in medicine. It was in Abbasid caliphate where the first hospitals and medical institutes were established. Down the centuries Muslim doctors have been ahead of the curve in studies of eye diseases. The first hospital in the caliphate was established as far back as 707, even before the Abbasid revolution. It should be also mentioned that it was state-funded: all the expenses for maintaining the hospital and supplying patients with food lay on the state. Leprous patients were arrested in order to prevent them from escaping. The famous Muslim scientist Ibn Sina (also known in the Western world as Avicenna) discovered numerous contagious diseases, anesthesia, the connection between the physical and mental condition of a human being. In 12-17 centuries his book was used as a textbook in the best European medical universities. The Muslim world is also a homeland for such science as chemistry. Jabir ibn Hayyan is considered to be a parent of chemistry. He described many acids and expressed his thought about the great energy hidden inside the atom and the possibility of its splitting. According to Hayyan, the power which is emitted when the atom is split is enough to destroy Baghdad.

It should be mentioned that the caliphate reached its economic and cultural prosperity during Harun al-Rashid’s ministry (785-809). The first period of his reign brought the state to prime of its glory with vigorously developing agriculture, handicraft, trade, culture. Harun al-Rashid founded a library and a university in Baghdad. In that time the caliphate extensively traded with many countries from China to Western Europe. Historians also mention that the caliph kept good terms with the king of Franks Charles the Great: the states exchanged embassies. The caliphate had special relations with Byzantium, too. Al-Rashid’s crusade and the defeat of the emperor Konstantin brought two states to a peace treaty which was quite humiliating for Byzantium. Konstantin’s successors refused to pay annual tribute to the caliphate, but it always leads to warfare and defeat. Later, the troops of the caliphate occupied Cyprus, Rhodes and the territory of modern Turkey. Apparently, this kind of relationships between the caliphate and Byzantium worked in Charles’ favor as he considered Byzantium to pose danger for his state, Roman Empire. The reign of Al-Rashid brought cultural and economic prosperity to the caliphate. Magnificent edifices were built across the capital, schools and hospitals were founded. Al-Rashid encouraged the development of music, science, and poetry. He invited celebrated scholars, doctors, musicians, and poets to the court with foreigners among them. According to the researchers, Abbas ibn al-Akhnaph, the poet, was rather close to Al-Rashid. And the caliph himself was fond of writing poems, too.

Except that, trades, agriculture, and commerce underwent intensive development. He introduced obligatory usage of paper in administrative management. In fact, the Islamic world adopted the practice of papermaking from Chinese civilization (Lucas, 2005). The practice of making and using paper came to the Muslim world in the 8th century. As the paper was easier to produce than parchment and more resistant than papyrus it proved to be perfect for making copies of the Qu’ran. According to Holland Cotter, Muslim paper makers introduced assembly-line methods for manuscripts that used to be hand-copied; that allowed them to produce the largest circulations in Europe for centuries" (Cotter).

But along with progress and development, antigovernment rebellions in various parts of the caliphate became more frequent, for instance, in Deylam, in Syria and in other parts of the caliphate. In 809 Harun Al-Rashid led his troops to suppress one of such uprisings that had flared up in Central Asia, but he got ill and died on the way in the city of Tus (territory of modern Iran). He was buried also there. His heirs were his three sons, the caliphate was divided between them, and they were expected to reign according to the line of priority. But in reality, al-Rashid’s death laid the foundations of the caliphate’s disunity. So, his eldest son, Al-Amin ascended to the throne and reigned till 813. But this caliph paid attention mostly to entertainments and neglected state affairs, due to this fact he was not very popular among the people. In 811 a conflict about the succession to the throne began between two brothers, Al-Amin and Al-Mamun. This conflict triggered a civil war, and Al-Mamun came out of it as a victor. A rather small army of Al-Mamun led by Takhir, the commander from Khorasan, defeated Iraq troops and moved westwards. The war lasted for two years. Al-Mamun’s army occupied all Western Iran and moved close to Baghdad. Then there was a two-year siege of the city. Al-Amin’s adherents supported by the citizens who were afraid of the Khorasan army resisted furiously as they thought the arrival of that army to be almost foreign intervention. The city fell in 813, and Al-Amin was put to death by Takhir’s soldiers. Al-Mamun was proclaimed a caliph.

This caliph was also known as a patron of science, the supporter of Mutazilites’ Muslim doctrine. Al-Mamun tended to involve scholars into the government of the state and founded the House of Wisdom in Baghdad (Iraq), which was a library, an academy and an institute of translation (Britannica). It was he at whose support the meridian arc was measured, an astronomic observatory was build and Ptolemy’s “Almagest” was translated to Arabic. Similar to the Umayyads, he commanded his deputies to govern provinces. During his reign, all the rebellions in the caliphate were severely suppressed. In 817 Baghdad citizens rose in rebellion against Al-Mamun and proclaimed Ibrahim ibn al-Makhdi a caliph, but in 819, after several months of siege, Al-Mamun captured the city, and Ibrahim ibn Al-Makhdi escaped.

When Al-Mamun fell ill and then died in August of 833, he was succeeded by his half-brother, al-Mutasim, the eighth Abbasid caliph who remained in power till his death in 842.

Muhammad al-Mutasim was the youngest son of Harun Al-Rashid born by a concubine of Persian origin. He was a boy when his father died. Growing up a purposeful and decisive person, he preferred to use all his resources to recruit soldiers who would be loyal to him alone, while his elder brothers spent a lot of time with poets and musicians. In 815 he began to form the army consisting only of the Turkish. First, he bought slaves in Baghdad and then – from the merchants in Central Asia. As a result, he got a firm military unit consisting of a few thousands of soldiers, disciplined and loyal to their commander. Al-Mutasim was the only one of the Abbasids to have such an army. When Al-Mamun was in power he served under him as a military commander and a governor in Egypt and other territories. According to Bosworth, his reign was marked by the introduction of the Turkish slave-soldiers and the establishment for them of a new capital at Samarra. This was a watershed in the Caliphate's history, as the Turks would soon come to dominate the Abbasid government (Bosworth, 1993).

It is uncertain if the previous caliph appointed him as his successor before death or he simply took favor of being near (while his son Al-Abbas was on another border of the empire) at that moment. Nevertheless, Al-Abbas refused the throne and adjured to his uncle. Al-Mutasim immediately stopped the campaign against Byzantium and returned to Baghdad (El-Hibri, 2011). The Turkish commanders became the key personalities for his regime. In autumn of 835, Al-Mutasim moved the capital 100km upstream of the Tigris River and erected there a new city – Samarra. Naturally, a new court was established there and the Turkish army with its commanders moved there, too.

At that time two centers of resistance appeared in the caliphate: Azerbaijan where Babak headed the rebellion and the south coast of Caspian Sea was local government tried to preserve the old-fashioned way of life. Al-Mutasim is especially famous by suppressing Babak’s rebellion. One of his Turkish commanders, Afshin defeated Babak, caught him and brought to Samarra for execution. Mazyar, the leader of the uprising on Caspian coast was also defeated, captured and brought to Samarra.

Al-Mutasim shared his brother’s views and was a supporter of Mutazilites’ doctrine; he considered Qu’ran to be created and continued with prosecution for those orthodox theologians who argued against the doctrine.

In fact, the end of Al-Mutasim’s reign became the beginning of the decline for the caliphate. Al-Mutasim was the last emperor to keep ultimate control in all the territories of the state and the only one to control the Turkish army as later they took much of power and made the caliphs puppets in their hands. After his death in 842, the court guard played the key role in the caliphate. Turks could either remove or appoint new governors who – in fact – were now of no importance. By the middle of the 10th-century power of the caliph spread only on the capital and the territories lying in the vicinity of it. And in 945 the throne was seized by the Buyids. They ruled the empire on behalf of the Abbasid who were deprived of temporal power, personal guard and family manors. The only thing that remained was a spiritual authority. Their position did not change after Seljuq conquest of Baghdad: caliph as a representative of spiritual power “appointed” temporal governors – sultans and emirs.

The period of Abbasid reign ended in 1258 when the Baghdad was sacked by the Mongols led by Hulagu Khan. After that, the caliphate and the Muslim culture changed their center from Baghdad to Cairo, the Mamluk capital. Though the dynasty had no actual power, they continued to claim authority in matters of religion, but even that ended when the Ottoman Empire conquered Egypt and the position of caliph was surrendered to its sultan.